Blog Post

Insight: COVID-19 and Air Quality

By: Thomas Holst

Note: The opinions expressed are those of the author alone and do not reflect an institutional position of the Gardner Institute. We hope the opinions shared contribute to the marketplace of ideas and help people as they formulate their own INFORMED DECISIONS™.

Oct 5, 2020 – Six months into the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly everybody’s daily habits have changed. Some changes such as mask wearing require strict discipline, while other changes have created pleasant surprises.

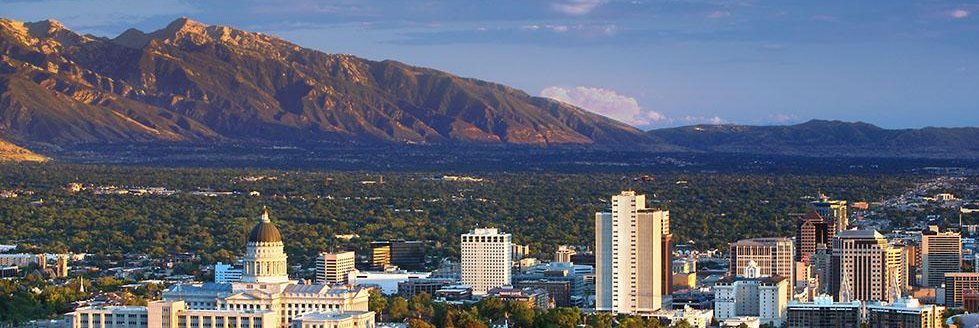

On the positive side, Salt Lake Valley air quality has improved due to reduced automobile traffic. On Friday mornings, my wife and I hike up to the ridge behind Ensign Peak. The clear view of the 25-mile-long Salt Lake Valley is more pleasant than viewing brown air trapped by an inversion lid. Teleworking has caused an estimated 40%–50% reduction in highway travel, which has improved air quality. Automobile tailpipe emissions decreased. Fine particulate matter, a criteria air pollutant that exacerbates asthma, decreased by 40%.[i]

COVID-19 has allowed employers to evaluate the effectiveness of teleworking. With increased localization of household activities, the number of bicycle trips in Utah spiked by 40%.[ii]

Areas outside the Wasatch Front also benefited. Reduced electricity demand in Utah decreased CO2 emissions from coal-fired power plants located south of the Wasatch Front.

On the negative side, just as quickly as air-quality improvements linked to COVID-19 appeared, Salt Lake Valley’s air quality degraded when winds carried smoke from California fires into the valley. Experts link California’s fires to increasing global temperatures spurred by climate change.

Air quality and climate change are two sides of the same coin, though each term generates different reactions among Utahns. On the one hand, poor air quality is regarded as a health threat and features in the top three issues identified by Utahns. On the other hand, many attribute increased temperatures to shifts in seasonality having no linkage to climate change.

A local example illustrates this point. Ice skating in Liberty Park was an enjoyable activity in 1920 (see Figure 1). The Liberty Park Bridge in the background is still familiar today, but the ice skating stopped many decades ago. For me, this striking image is evidence of a local climate change that occurred within the span of a lifetime. For others, increased temperatures are the “new” normal.

Figure 1: Free Municipal Skating Pond, Liberty Park, 1920

Source: Salt Lake City Municipal Record, January, 1920

COVID-19 has been a natural experiment when emissions dropped abruptly, allowing scientists to study the impacts on air quality and ecosystems.

Dr. Logan Mitchell, Research Assistant Professor at the University of Utah’s Department of Atmospheric Sciences, summed up developments to date: “The results give me a lot of optimism about the future. It shows that as we recover from the pandemic, if we invest in clean energy and electric vehicles, it’s really possible to clean up the air.”

Thomas Holst is the senior energy analyst at the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute.

[i] Air Quality Improvements During the March–April COVID-19 Lockdown, University of Utah Department of Atmospheric Sciences, https://atmos.utah.edu/air-quality/covid-19_air_quality.php

[ii] Long-term Transportation, Land Use, and Air Quality Impacts of COVID-19, Wasatch Front Regional Council.