Blog Post

Insight: What Negative Oil Prices Really Mean

By: Thomas Holst

Note: The opinions expressed are those of the author alone and do not reflect an institutional position of the Gardner Institute. We hope the opinions shared contribute to the marketplace of ideas and help people as they formulate their own INFORMED DECISIONS™.

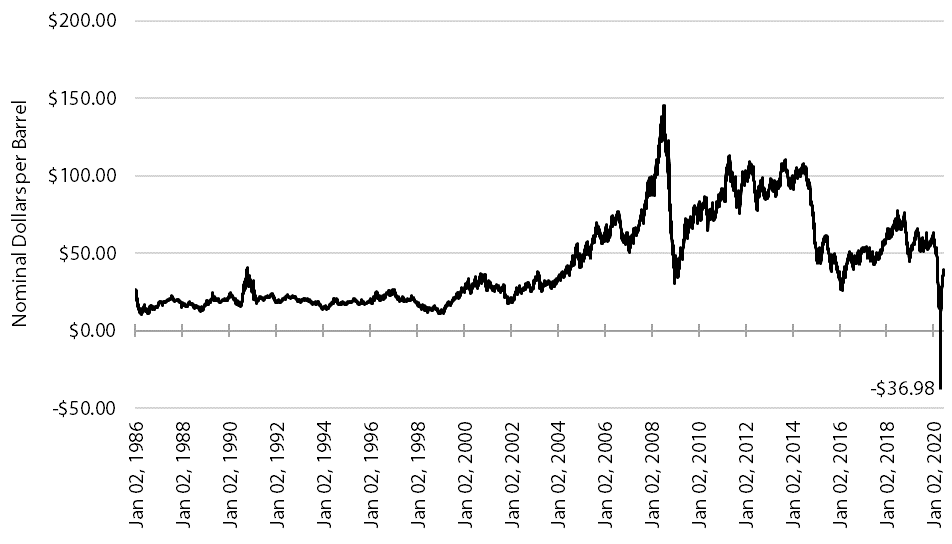

Jun 19, 2020 – COVID-19 has threatened both livelihoods and lives as well as causing surprises in energy markets. West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil prices sank into negative territory on April 20 for the first time in history (see Figure 1). How could negative crude oil pricing happen and who are the beneficiaries?

Two economic shocks caused energy prices to trend lower. First, crude oil markets suffered a supply shock when oil glutted the market because of a dispute between Saudi Arabia and Russia over global market share. Second, a demand shock created by COVID-19 reduced consumption of motor gasoline and jet fuel. Too many barrels of crude oil overwhelmed diminishing demand.

Figure 1: Cushing, Okla., WTI Spot Price, 1986–2020

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration/Thomson Reuters

Did the intrinsic value of WTI go negative on April 20? No. An explanation of the crude oil trading market will explain the negative crude oil pricing phenomenon.

On one hand, crude oil trades on a physical market in which buyers and sellers exchange barrels of WTI crude oil by pipeline, rail, or ship.

On the other hand, in parallel with the physical market, a “paper” crude oil market trades on the Chicago and New York Mercantile Exchanges for the benefit of speculators and hedgers (i.e., people seeking to lay off risks of price changes). Each “paper” contract requires either the delivery or receipt of 1,000 barrels of WTI crude oil into Cushing, Oklahoma tank storage.

Since neither speculators nor hedgers have physical facilities to receive or deliver WTI, they close out their trading books before the last day of the trading month.

On April 20, a few speculators or hedgers who bought paper contracts of WTI waited until the last day of the trading month to close out their trading books. Cushing, Oklahoma’s storage capacity of 76 million barrels was nearly full due to the global crude oil glut created by COVID-19. When these unfortunate speculators and hedgers sold their WTI paper contracts, they paid buyers a premium of $36.98 per barrel in order to close out their trading books.

Did the value of physical WTI crude oil diminish? No, because the following day the physical market resumed trading at $15 per barrel.

Who benefited from the premium paid by distressed “paper” traders? A few fortunate physical traders with spare crude oil storage capacity in Cushing, Oklahoma pocketed profit.

Under normal conditions, physical market prices converge with the paper market prices on the last day of the trading month. However, in this novel case, a few speculators and hedgers learned a costly lesson about closing out their trading books well before the final day of the trading month.

Thomas Holst is the senior energy analyst at the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute.