Blog Post

Insight: What Goes Up Must Come Down? The Muddled Post-Pandemic Inflation Picture

By: Phil Dean

Note: The opinions expressed are those of the author alone and do not reflect an institutional position of the Gardner Institute. We hope the opinions shared contribute to the marketplace of ideas and help people as they formulate their own INFORMED DECISIONS™.

Aug 26, 2021 – More than any time in recent memory, inflation is a hotly debated economic topic. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) July price change as measured by the seasonally adjusted Consumer Price Index (CPI) shows a 5.3% year-over-year overall increase (5.4% when not seasonally adjusted).

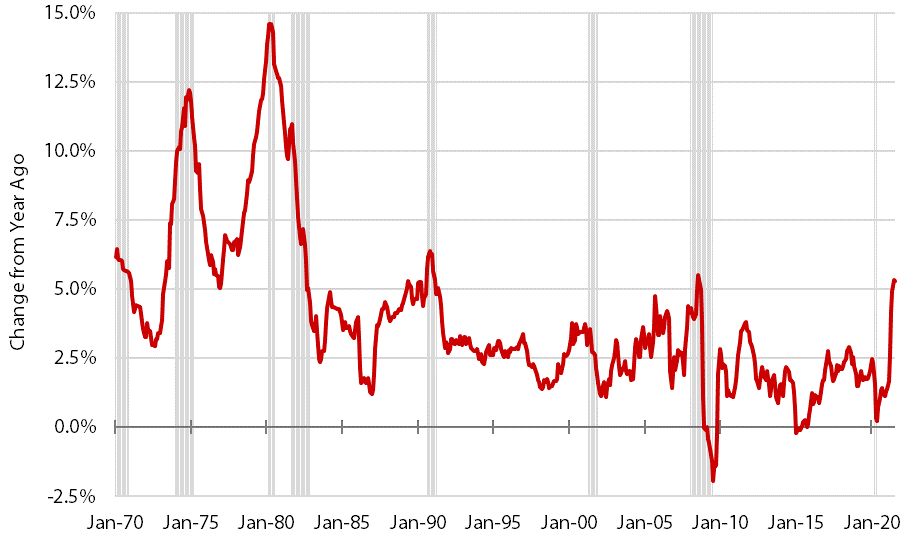

The July reading follows revised CPI growth estimates of 5.3% in June, 4.9% in May, and 4.2% in April. This elevated inflation trend (see Figure 1) has ignited debate about inflation’s future trajectory, focused primarily on whether the increases will be lasting or “transitory” (in the Federal Reserve’s parlance). Higher inflation’s expected duration has critical implications for the federal government’s fiscal policy and the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy.

Figure 1: Year-Over CPI Inflation Rate, January 1970 to July 2021

Note: Gray bars indicate recessions.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and National Bureau of Economic Research;

retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/

Unpacking Inflation Data

While in recent months inflation jumped to the highest levels in over a decade, the pandemic’s unique economic effects complicate predictions of future inflation. Even in good economic times, prices for the diverse goods included in the CPI increase and decrease differently depending on sector-specific dynamics and interactions between sectors. The pandemic exacerbated these effects.

Over the past 18 months, household spending patterns shifted from pandemic-curtailed services such as entertainment and travel to recreation and home-oriented goods, including sporting goods, recreational vehicles, and materials for landscaping, gardening, and home improvement. At the same time, pandemic-influenced shutdowns hit supply chains for most goods, with effects ranging from idled lumber mills to shipping and other production constraints. This led to major backlogs and delays from suppliers worldwide.

Used cars, which show a very large year-over price increase of nearly 42% as of July 2021, provide an example. A combination of pandemic-influenced factors drove this enormous price increase, including massive supply chain disruptions, consumers flush with cash to spend, and car rental companies initially selling and then buying cars en masse.

“Base effects” also make simple inflation comparisons challenging. The year-over comparisons in recent months are to some of the most pandemic-restricted months in 2020, when overall inflation was near zero and some sectors’ prices declined significantly.

For example, lodging away from home (hotels and motels) shows a July 2021 year-over 24% price increase. But compared with July 2019 lodging prices, July 2021 hotel prices are up only about 5%. That is, most of the current year-over price increase represents recovery from pandemic-driven price drops in 2020.

Energy commodities such as gasoline show a year-over price increase of over 41%, coming on the heels of a large 2020 price drop as demand tanked when the pandemic took hold. Although the two-year price increase of nearly 13% is still sizable, it is much smaller than the single-year increase.

Inflation Drivers

So while consumer prices clearly increased compared with last year, some argue that current inflation relates to unique economic circumstances that will not necessarily continue going forward. Clouding the picture (and adding to the debate), expansionary fiscal and monetary policy provided extra spending money layered on top of supply- and demand-driven shifts. Moreover, trillions more in federal deficit spending previously authorized but unspent, along with new deficit spending proposals totaling over $4.5 trillion, further cloud the inflation outlook.

All of these unconventional situations create challenges in determining what drives these recent price increases—pandemic-driven economic effects that could work themselves out in coming months, or economic policy decisions such as stimulus checks and low interest rates that may have more lasting effects.

Expectations Heavily Influence Behavior

Expectations drive people’s economic behavior. If I expect home prices to be much higher next year, I may feel urgency to accelerate my future planned home purchase to today. Conversely, if I expect home prices to drop next year, I may delay my purchase until after that price decline. In other words, people’s changed perceptions about the future can change economic outcomes today.

Producer Expectations. For many producers, the pandemic revealed supply chain vulnerabilities. Consequently, many firms are currently re-examining “just in time” approaches and looking to build more supply chain resiliency by reshoring to the United States and shifting and broadening overseas supply chains to more reliable partners. However, these supply chain shifts could translate into higher prices since these more resilient approaches may increase costs.

Consumer Expectations. Inflation has shifted from an obscure topic only economists discuss to mainstream conversations at water coolers and neighborhood potluck dinners. After decades of assuming inflation would remain low and relatively steady, warning signs suggest the beginning of consumer inflation expectations becoming unanchored to prior expectations of low and stable inflation.

For example, a recent Deseret News article indicates that 85% of Utahns are concerned about inflation, with a majority indicating they are very concerned about inflation. In addition, a consumer expectation survey by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York shows a sizable increase in short-term inflation expectations. Although this does not yet fully translate to long-term inflation expectations, that could happen quickly if inflation continues. The risk is that inflation expectations become self-fulfilling prophecies when consumer behavior adjusts as if the changes have already occurred, thereby causing those changes to actually occur.

However, a countervailing trend offsetting these concerns about an overheating economy creating persistent inflation is a recent consumer sentiment survey from the University of Michigan, which shows one of the largest drops in U.S. consumer confidence in history in early August 2021. A similar Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute survey for Utah shows a moderate July decline. While preliminary, if this confidence decline translates into consumption declines, this would reduce inflationary pressures.

Moving Forward

Inflation will remain top of mind given recent increases in prominent prices people watch closely. Assuming the pandemic continues to be brought under control through expanded vaccinations, the next six to nine months will provide a clearer indication of whether inflation is here to stay or a temporary blip.

Phil Dean is the public finance senior research fellow at the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute.