Blog Post

Insight: Oral Health in Utah

By: Julia Martin

Mar 21, 2022 – “Good oral health is critical for children, as it can affect their overall health, social adjustment, appearance, school performance, and ability to thrive”[1]

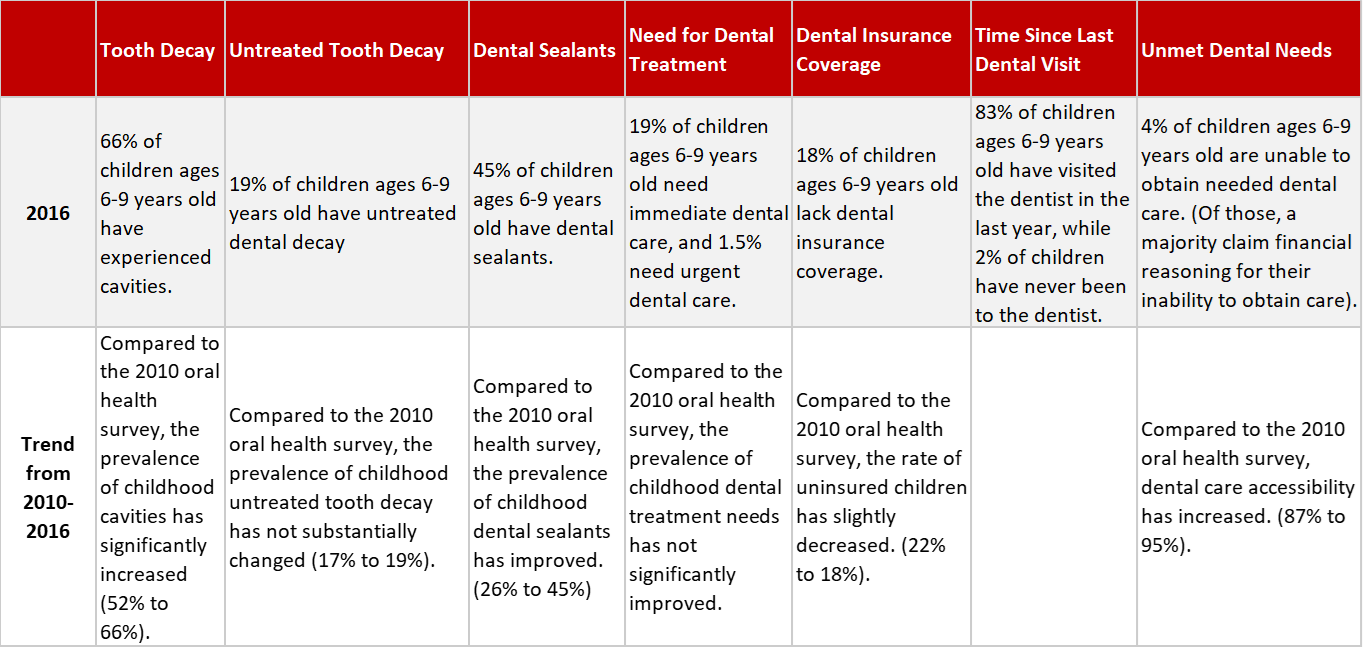

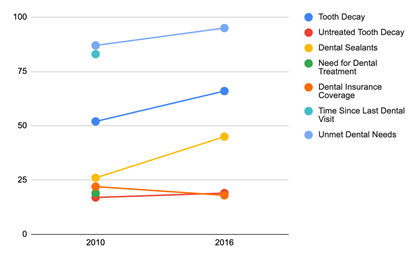

Oral health is an often overlooked and ignored health status in Utah. The state’s most recent oral health campaign focused on Utah adolescents,[2] while this is a step in the right direction, there needs to be a bigger emphasis on childhood oral health. Unfortunately, the most recent data for childhood oral health is from the 2015-2016 Oral Health Status of Utah’s Children. According to this report, there is a “concerning level of oral disease among Utah elementary school children”[3] (refer to Table 1 for a general summary of childhood oral health). These concerning childhood oral health discoveries are further correlated with racial/ethnic minority status, federally funded public health insurance, and geographic location.

Dental Sealants

“A person’s ability to access oral health care is associated with factors such as education level, income, race, and ethnicity”[4]

Dental sealants are a low-cost and integral intervention of preventative dental care. Dental sealants help inhibit and reduce the effect of cavities. There are serious and visible disparities in childhood oral health when one accounts for the utilization of dental sealants. Children enrolled in Medicaid have a higher percentage of cavities experienced (75.6% vs. 63.9% for private insurance). A likely determinant of this high cavity occurrence is the decreased utilization of dental sealants – 32.9% of children on Medicaid have dental sealants while nearly 50% (49.3%) of Children on private insurance have dental sealants. Furthermore, children of racial and ethnic minorities have a lower utilization rate of dental sealants (33% vs 45%).[5] Specifically, Hispanic children are more likely to experience untreated tooth decay (25% vs. 18% for their non-Hispanic counterparts) and have greater unmet dental needs (15% vs 4%). These high prevalence rates can be attributed to the higher likelihood that children of Hispanic origin do not have dental insurance (26% of children from Hispanic origin do not have dental insurance).[6] Children who qualify for Free and Reduced Lunch programs likewise have higher rates of untreated tooth decay and cavities.[7] This reaffirms the need for increased dental sealant utilization and accessibility for underserved racial/ethnic minority children.

Disparities by Geography

“Where an individual resides and works can improve or limit access to oral health services”[8]

Oral health disparities are not confined by race/minority status. There is a severe disparity in access to care and services between rural and urban areas. Rural areas face health care professional shortages along with shortages in healthcare and transportation infrastructure.[9] A recent study looking at the oral health status of Utah’s health professional shortage areas (HPSAs) claims that 66% of Utah counties are dental HPSAs. This study further concludes that nearly half of individuals living in HPSAs are in need of oral health care and that over half (60%) of this population struggle to acquire appropriate oral health care.[10] There is a disproportionate number of dentists working in urban counties compared to rural counties in Utah. 11.1% of Utah’s dentist workforce practice in rural counties despite 15.4% of Utah’s population residing in those same counties.[11]As of 2017, Salt Lake County has a distribution surplus of dentists, (43.7% of the workforce) far outpacing any other Utah county (the closest being Utah County at 18.6% of the workforce).[12]

The Costs of Dental Disease

Utah data clearly exhibits the immediate need for oral health improvement. Dental diseases must be considered a major public health concern. Ignoring oral hygiene is costly. Patients who are unable to receive routine dental care are more likely to visit the emergency department. In line with the urban/rural divide explained above, oral health-related visits to the emergency department occur at a significantly higher rate in rural hospitals. These non-traumatic emergency department visits for dental care cost the state on average $52 million yearly.[13] Since emergency departments are not equipped to administer dental services, most of these patients are only treated for pain – not the actual cause of the dental complaint – resulting in continued dental decay and emergency department usage. These costs could be largely mitigated if patients were able to afford routine dental care.

Poor oral health is a downward reinforcing spiral. Good oral health is integral for everyday functions such as speaking, smiling, and eating.[14] Poor dental hygiene severely impacts individuals, communities, and futures. Maintaining good oral hygiene is imperative to overall general health and well-being. Financial prosperity is likewise connected to oral health. Nationwide, children experiencing poor oral health “miss approximately 51 million hours of school each year”.[15] This severely inhibits their educational and future success attainability. Additionally, poor oral health affects the nutritional health of children.[16] The pain caused by dental decay inhibits a child’s ability to eat and receive proper nutrition.

There is a need to expand oral health research and recognize the connection between oral and overall health. The disparity of oral health care in terms of access and affordability is costly to the state and residents. The connections between childhood oral health and education health and success attainability must be recognized to curb the enduring costs of care.

Table 1

Source: Utah Department of Health, Division of Family Health and Preparedness, Oral Health Program and Data Resources Program. The 2015-2016 Oral Health Status of Utah’s Children. November 2016. Retrieved from the Utah Department of Health.

Julia Martin is an intern at the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute and studying Political Science and Psychology at the University of Utah

Note: The opinions expressed are those of the author alone and do not reflect an institutional position of the Gardner Institute. We hope the opinions shared contribute to the marketplace of ideas and help people as they formulate their own INFORMED DECISIONS™.

[1]Institute of Medicine (US) Board on Health Care Services. The U.S. Oral Health Workforce in the Coming Decade: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2009. 3, Current Oral Health Needs and the Status of Access to Care. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK219678/?report=reader

[2]Neufeld, L., Silver, M., & Cotton, M. (2020). (rep). 2019-2020 Adolescent Oral Health

Campaign. Utah Department of Health. Retrieved from https://health.utah.gov/oralhealth/resources/reports/2019-2020%20-%20Adolescent%20Oral%20Health.pdf

[3]Utah Department of Health, Division of Family Health Preparedness, Oral Health Program and

Data Resources Program. The 2015-2016 Oral Health Status of Utah’s Children. November 2016. Retrieved from https://health.utah.gov/oralhealth/resources/reports/2015-2016%20Oral%20Health%20Survey.pdf

[4]U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). Oral Health. Retrieved from Healthy People 2020 Topics and Objectives: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/oral-health

[5] Utah Department of Health, Division of Family Health Preparedness, Oral Health Program and

Data Resources Program. The 2015-2016 Oral Health Status of Utah’s Children. November 2016. Retrieved from https://health.utah.gov/oralhealth/resources/reports/2015-2016%20Oral%20Health%20Survey.pdf

[6] Utah Department of Health, Division of Family Health Preparedness, Oral Health Program and

Data Resources Program. The 2015-2016 Oral Health Status of Utah’s Children. November 2016. Retrieved from https://health.utah.gov/oralhealth/resources/reports/2015-2016%20Oral%20Health%20Survey.pdf

[7] Utah Department of Health, Division of Family Health Preparedness, Oral Health Program and

Data Resources Program. The 2015-2016 Oral Health Status of Utah’s Children. November 2016. Retrieved from https://health.utah.gov/oralhealth/resources/reports/2015-2016%20Oral%20Health%20Survey.pdf

[8] Office of Health Disparities. Addressing Oral Health Disparities in Urban Settings: A Strategic Approach to Advance Access to Oral Health Care. Salt Lake City (UT): Utah Department of Health, Office of Health Disparities; January 2018. Retrieved from https://health.utah.gov/disparities/data/ohd/SPIWhitePaper2018.pdf

[9] Office of Health Disparities. Addressing Oral Health Disparities in Urban Settings: A Strategic Approach to Advance Access to Oral Health Care. Salt Lake City (UT): Utah Department of Health, Office of Health Disparities; January 2018. Retrieved from https://health.utah.gov/disparities/data/ohd/SPIWhitePaper2018.pdf

[10] Pinzon, L.M., Petukhova, Y., Pham, S., Knighton, R.., He, J., Phan, H.T., Garcia-Godoy, F., Rackham, L., & Power, J.M. (2021). Oral Health Status of a Utah Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) Population. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-500508/v1

[11] Utah Medical Education Council (2017). Utah’s Dentist Workforce, 2017: A Study of the Supply

and Distribution of Dentists in Utah. Salt Lake City, UT. Retrieved from https://umec.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/Utah-Dentist-Workforce-Report-2017-1.pdf

[12] Utah Medical Education Council (2017). Utah’s Dentist Workforce, 2017: A Study of the Supply

and Distribution of Dentists in Utah. Salt Lake City, UT. Retrieved from https://umec.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/Utah-Dentist-Workforce-Report-2017-1.pdf

[13] Oral Health Program (2019). An Analysis of Utah’s Emergency Department Non-traumatic Dental Visits 2007-2017. Retrieved from https://health.utah.gov/oralhealth/resources/reports/2019%20-%20UDOH%20Analysis%20of%20Emergency%20Dept%20Non-traumatic%20Dental%20Visits.pdf

[14]Baiju, R. M., Peter, E., Varghese, N. O., & Sivaram, R. (2017). Oral Health and Quality of Life: Current Concepts. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR, 11(6), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2017/25866.10110

[15]Institute of Medicine (US) Board on Health Care Services. The U.S. Oral Health Workforce in the Coming Decade: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2009. 12, A Charge to Improve Children’s Access to Oral Health Services. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK219660/?report=reader

[16] Institute of Medicine (US) Board on Health Care Services. The U.S. Oral Health Workforce in the Coming Decade: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2009. 12, A Charge to Improve Children’s Access to Oral Health Services. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK219660/?report=reader