Blog Post

Insight: Economic Development and the American Dream

By: Max Backlund

Note: The opinions expressed are those of the author alone and do not reflect an institutional position of the Gardner Institute. We hope the opinions shared contribute to the marketplace of ideas and help people as they formulate their own INFORMED DECISIONS™.

May 20, 2021 – In simpler days, economic development meant adding new jobs and pursuing new tax revenue, but in recent years it has grown to incorporate goals like improving quality of life and upward mobility. For instance, the 2016 Strategic Plan for the Utah Governor’s Office of Economic Development (GOED) included this mission statement:

“Enhance the quality of life by increasing and diversifying Utah’s revenue base and improving employment opportunities.”[1]

In 2019, GOED revised their economic development strategy, including a much broader mission statement:

“Building on its success, Utah will elevate the lives of current and future generations through an exceptional quality of life, provide economic opportunity and upward mobility, and encourage business growth and innovation. Utah is home to attractive, healthy urban and rural communities where residents and businesses thrive, and visitors feel welcome.”[2]

This more comprehensive vision places a greater burden on economic development efforts to go beyond new jobs and wages to include upward mobility and thriving communities for current and future generations. In 2016, GOED’s plan was four pages, including the front and back covers. In 2019 the plan grew to 42 pages. This new, enhanced set of goals raises questions about the connection between upward mobility and economic development. I offer three insights into this connection.

- Historically, Salt Lake City has led the nation in upward mobility. In 2014 a group of researchers from Stanford and Harvard universities, led by Dr. Raj Chetty, identified the Salt Lake City area as having the highest rate of intergenerational income mobility. Key factors for Utah included high rates of social capital, higher rates of family stability, and lower income inequality.[3]

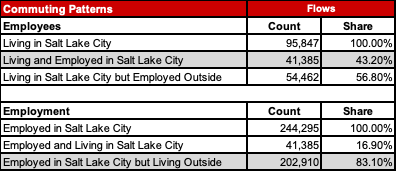

- Tying economic development to upward mobility is difficult in urban centers, like Salt Lake City, where a majority of jobs are held by nonresident commuters. Traditional economic development efforts to create jobs may not directly reach residents of Salt Lake City, only 43% of whom also work in Salt Lake City. Of the city’s approximately 244,000 jobs, more than 83% are filled by nonresident commuters (see Table 1).

Table 1: Salt Lake City Commuting Patterns, 2018

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, OnTheMap

- High economic growth, by itself, does not create substantial upward mobility. Another study by Dr. Chetty and his research team shed light on historic rates of upward mobility. Intergenerational income mobility rates have declined from 90% for children born in the 1940s to less than 50% for children born in the 1980s.[4] Nationally, millennials are significantly less wealthy than previous generations were at the same age. Even now, as the largest demographic cohort, millennials own about 4.6% of wealth in the U.S., where baby boomers owned 21% at the same age.[5] Millennials may be the first generation in decades to earn less money than their parents. This trend affects marriage rates, fertility rates, and home ownership—all key indicators for quality of life.[6]

What has historically worked for economic development and upward mobility in Utah may not be enough to overcome the challenges facing millennials. Public- and private-sector leaders will need to work across industries, economies, and geographies to ensure that Utah’s historic growth leads to greater opportunity and upward mobility.

Max Backlund is a senior research associate at the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute.

[1] Chetty, R. et.al. (2016). The Fading American Dream: Trends in Absolute Income Mobility Since 1940. Harvard University: Opportunity Insights. Retrieved from https://opportunityinsights.org/paper/the-fading-american-dream/

[2] Adamczyk, A. (2020, October 9). Millennials own less than 5% of all U.S. Wealth. CNBC. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/10/09/millennials-own-less-than-5percent-of-all-us-wealth.html

[3] Lowery, A. (2021, May 13). Why Millennials Can’t Grow Up. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/05/millennial-grandparents-unequal-generation/618859/

[4] Utah Governor’s Office of Economic Development. “Strategic Plans 2016-2020.” Retrieved from https://issuu.com/goed/docs/strategicplan2016-2020final.compressed

[5] Utah Governor’s Office of Economic Development. “A Plan to Elevate Utah’s Economic Success.” Retrieved from https://issuu.com/goed/docs/utah-goed-2019-strategic-plan

[6] Chetty, R. et al. (2014). Where is the Land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(4): 1553-623. Retrieved from: http://www.rajchetty.com/chettyfiles/mobility_geo.pdf