Blog Post

Insight: Does Utah Have a Housing Shortage?

By: James Wood

Several housing market indicators suggest Utah may have a housing shortage:

- Home sales are hot. In the past two and a half years, the typical “for sale” home sold in 25 days.

- Prices of “for sale” homes continue to climb at a brisk pace. Home prices along the Wasatch Front counties are up nearly 25 percent in three years, pushed up by demand running ahead of supply.

- The number of new listing of “for sale” homes have been disappointing. Sharply rising prices generally bring more sellers into the market and boosts the number of listings but listings have lagged well below demand limiting home buyer choices.

- Apartment vacancy rates are at the lowest level in decades despite the historic apartment boom. The boom has added 20,000 units statewide since 2012, a seven percent increase in the rental inventory but the rental market remains extremely tight.

- Apartment rents are increasing at five to eight percent annually in many markets and rents have topped $2.00 a square foot in downtown Salt Lake City and Sugarhouse. To date, however, there has been very little market resistance to high rents.

- Home builders have virtually no unsold inventory and are producing at full capacity.

- The supply of new homes is held back, according to builders, by serious labor shortages, high land prices, and municipal zoning, fees and regulations.

And then there’s the recently released demographic data by the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute, perhaps the most compelling indicator of a housing shortage. The demographic data, in this case household growth, identifies the likely cause of a housing shortage rather than adding to the list of symptoms given above. According to the recent demographic data, household growth has been stronger than previously thought. This is very important news for the home building industry, local municipalities, and policy makers.

Household growth is the principal driver of demand for new residential construction. Each additional household creates demand for an additional housing unit, whether that household comes from net in-migration, a marriage, a divorce, or a child leaving home to live on his/her own. The number of households, at least in theory and as reported by the U.S. Census Bureau, is the same as the number of occupied housing units.

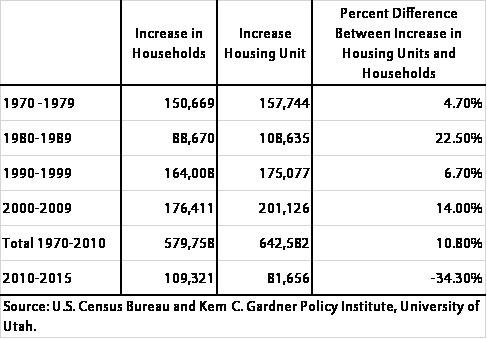

As the number of households increases, the number of housing units should also increase by roughly a similar amount, with the increase in housing units being a bit larger than the increase in households. The difference is due to vacant units (vacant for sale, vacant for rent, and vacant for seasonal or recreational use). Over a span of 40 years, from 1970 to 2010, the increase in housing units in Utah was 11 percent higher than the increase in households; a reasonably close association between additional housing units and households. In every decade since 1970, the increase in housing units has been larger than the increase in households (see Table 1). But this long-time relationship has been upended in the past five years. The number of households has increased by 109,321 since 2010, while the number of housing units has increased by only 81,656. For the first time in over 40 years, households are increasing at a faster pace than housing units; a strong signal of a housing shortage.

Table 1: Change in Households and Housing Units in Utah

James Wood is the Ivory-Boyer Senior Fellow at the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute.