Blog Post

Insight: Utah’s Uninsured Population May Look Different After the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency Ends

By: Laura Summers

Note: The opinions expressed are those of the author alone and do not reflect an institutional position of the Gardner Institute. We hope the opinions shared contribute to the marketplace of ideas and help people as they formulate their own INFORMED DECISIONS™.

One thought that struck me as I was preparing for a recent meeting was how the characteristics of Utah’s uninsured population may have changed over the last year and a half―and how we don’t yet know what Utah’s uninsured population will look like until the public health emergency ends. This is due to several federal and state policies that have been enacted since January 2020, as well as external factors that could impact the uninsured in Utah. For example:

- Full Medicaid expansion became effective in Utah in January 2020. This means any individual with income below 133% of the federal poverty level (FPL) is eligible for Medicaid coverage.[i] Data from the Utah Department of Health show Medicaid enrollment has steadily increased since the beginning of 2020.[ii]

- However, some of this increase is due to the Medicaid continuous coverage requirement associated with the public health emergency. In order for states to receive an enhanced federal financial match for their Medicaid programs, they cannot discontinue coverage for most Medicaid enrollees while the public health emergency is in place, regardless of changes in a person’s eligibility. At this time, the public health emergency will continue until at least October 2021, meaning Utah’s Medicaid rolls won’t see a drop due to eligibility changes until this fall.

- There are several provisions in the federal American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) that increase access to health insurance. For example, ARPA expands eligibility for Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace subsidies to individuals with income above 400% FPL. Subsidies vary based on income, but limit household income spent on a Marketplace plan to 8.5%. Prior to ARPA, individuals with income above 400% FPL were not eligible for subsidies. This policy, and related changes that increase subsidy amounts for lower-income populations, remain in effect for calendar years 2021 and 2022. Additionally, between April 1 and September 30, 2021, employers are responsible for covering 100% of an employee’s cost of continuing group health coverage under COBRA if that employee lost their health insurance due to a reduction of hours or an involuntary termination.

- While COVID-19 increased unemployment and decreased access to health insurance, it’s important to note that Utah’s uninsured rates were actually increasing before the pandemic. For example, a report from the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families found that Utah experienced a 39% increase in the number of uninsured children between 2016 and 2019.[iii] Similar trends were seen in the adult population, which is confusing given this was a period when unemployment was generally decreasing and ACA provisions were still largely in place. It will be interesting to see whether the policies noted above increase access to health insurance sufficiently to counteract this previous upward trend in uninsured rates.

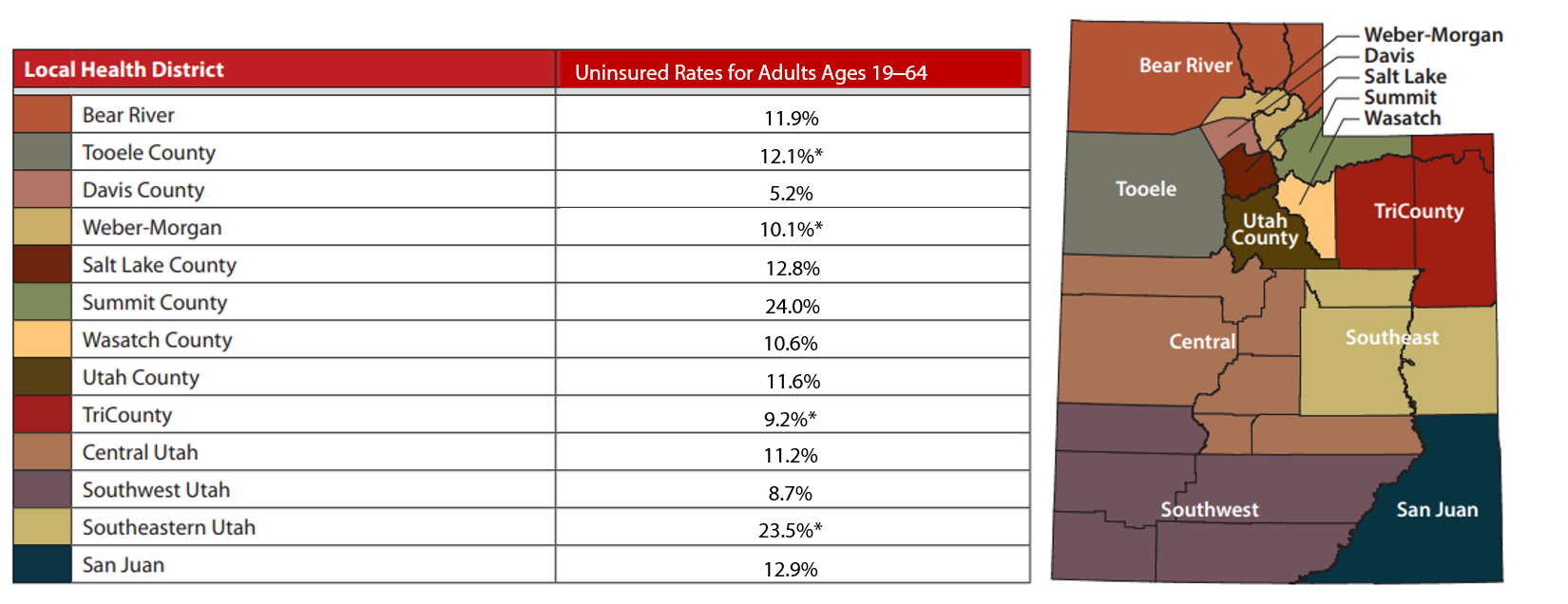

- As with any indicator, there are a lot of nuances to consider. For example, Utah’s uninsured rates vary significantly based on age, education level, race, ethnicity, and geography (see Table 1). For example, in 2019, the Davis County Local Health District had the lowest uninsured rate among adults age 19‒64 (5.2%). Summit County Local Health District had the highest (24%). While Utah’s economy as a whole fared relatively well during the pandemic, some industries and areas were hit harder than others. Additionally, some of Utah’s rural economies could be facing significant transitions in the next 5‒10 years as energy-, natural resources–, and mining-based industries change.

Table 1: Utah Uninsured Rates for Adults Ages 19‒64, 2019

Note: Health insurance is defined as including private coverage, Medicaid, Medicare, and other government programs. Data is not age-adjusted.

*Use caution in interpreting. The estimates have a relative standard error greater than 30% and are therefore deemed unreliable by Utah Department of Health standards.

Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Office of Public Health Assessment, Utah Department of Health. Retrieved Monday, 2 August 2021 from the Utah Department of Health, Indicator-Based Information System for Public Health Web site: http://ibis.health.utah.gov.

Utah’s uninsured population could look very different from what it did two years ago. As the public health emergency comes to an end, and federal policies that currently provide a buffer for the uninsured phase out, Utah’s policy and health system leaders should gain a better understanding of who the uninsured population is in Utah and what policies are needed to address barriers to accessing health insurance. That said, it is important to note that access to insurance does not necessarily equal access to adequate care. As such, Utah’s policy and health system leaders should simultaneously continue to look beyond Utah’s uninsured rates to understand if and why Utahns are unable to access the health care they need, whether they have access to health insurance or not.

Laura Summers is the senior health care analyst at the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute.

[i] Note: income thresholds are higher for some children and adult populations.

[ii] http://www.healthpolicyproject.org/wp-content/uploads/Medicaid-Trends-12.pdf

[iii] https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2020/10/08/childrens-uninsured-rate-rises-by-largest-annual-jump-in-more-than-a-decade-2/