Blog Post

Insight: Utah’s Challenge

By: Phil Dean

Note: The opinions expressed are those of the author alone and do not reflect an institutional position of the Gardner Institute. We hope the opinions shared contribute to the marketplace of ideas and help people as they formulate their own INFORMED DECISIONS™.

Utah’s population and economy continue growing. This growth creates tremendous opportunities for Utahns. Growth also creates challenges. Some growth challenges stem from the interactions of topographical and other physical constraints with legacy transportation, land, air, and water use patterns. Other challenges arise because outdated systems poorly align with the modern economy. Yet transformational economic changes continue unabated.

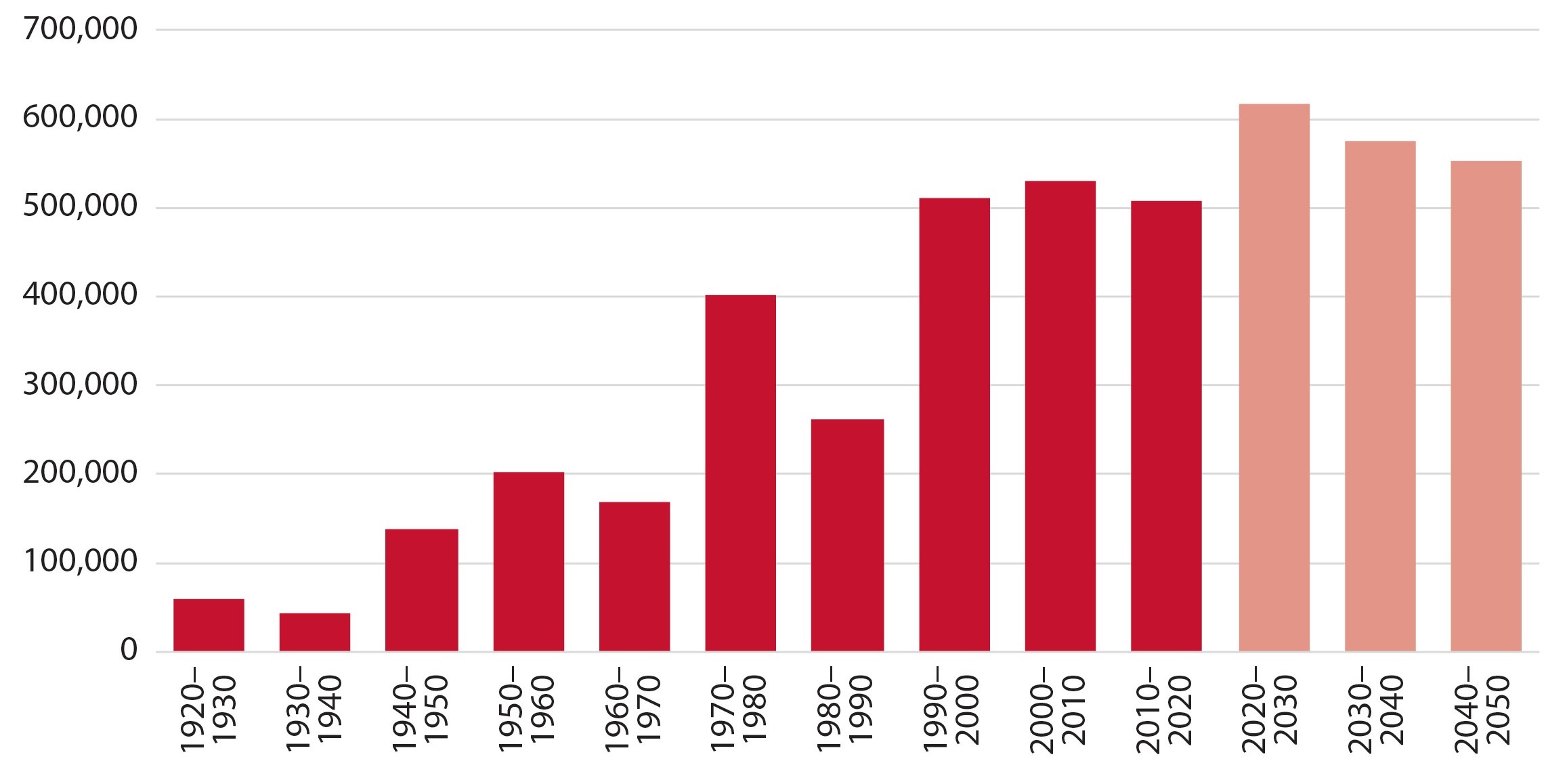

Figure 1: Utah Population Change by Decade, 1920–2050

Source: Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute 2017 Population Projections

Source: Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute 2017 Population Projections

These pressures require constant adaptation, innovation, and realignment of Utah’s fiscal systems to ensure essential services continue. Utah’s leaders face critical design decisions as they generate and spend public funds for transportation, water, education, and other public services vital to Utah’s high quality of life.

User Fees vs. Taxes

In the private sector, prices ration scarce resources, sending signals to suppliers about how much to produce and to demanders about how much to buy. But unlike voluntary purchases in the private sector, government compels people to pay taxes. Taxes harm economic efficiency, but at the same time generate revenue needed to supply critical services supporting the economy.

Like taxes, government user fees also generate revenue to pay for critical services. But when designed well, fees can enhance economic efficiency by matching service demands with funding to supply those services, similar to the private market. In other words, all government revenue sources are not created equal. Different ways of paying for government create different economic effects.

User Fee Design

Even among fees, not all fees are created equal. Some fees are very distant from usage levels and function more like taxes, while others are much more closely aligned with usage levels. For example, a mileage-based road usage charge is much more closely aligned with use than an annual car registration fee, which is more of an ownership fee than a true usage fee.

Properly constructed user fees harness the power of market prices to align the demand and supply of certain government services, allowing people to select their desired level of service. In other words, fees can allow some areas of government to run more like a business. People can pay less for government services by changing their behavior to use less, or pay more to use more. Like payments in the private market, this element of choice can increase economic efficiency, fairness, and quality. The key is to structure user fees to properly place incentives, minimize collection costs, address regressivity, and maximize public acceptability.

Utah’s User Fee Levels

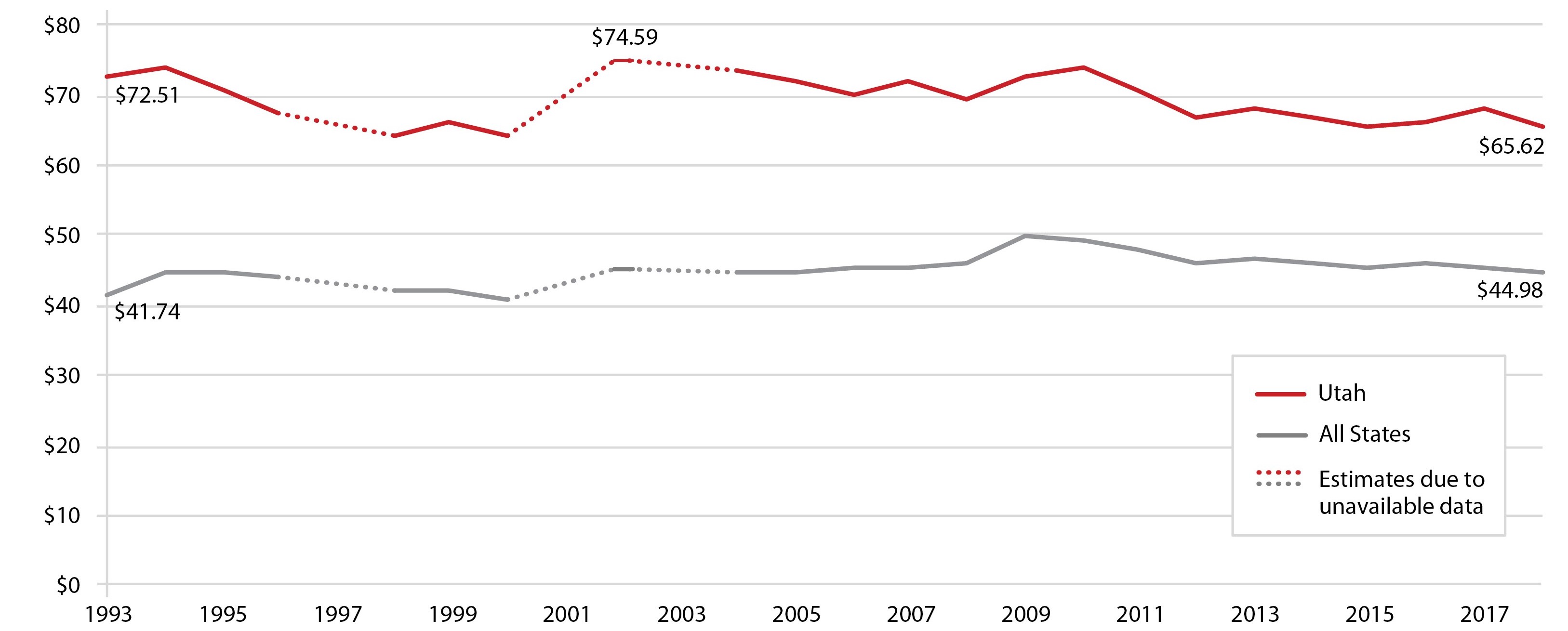

Even with the many desirable attributes of user fees compared with taxes, Utah’s reliance on user fees relative to personal income has declined in recent decades, as shown below. Utah’s comparatively high reliance on fees overall compared with other states is primarily due to tuition fees paid by Utah’s younger population (despite lower tuition rates overall), hospital system fees at the University of Utah, and charges for publicly supplied electricity. Conversely, Utah relies less on fees for transportation and for certain utilities such as sewer.

Figure 2: Fees per $1,000 of Personal Income, 1993–2018

Note: Data unavailable for 1997, 2001 and 2003, so graph includes estimates for these years.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances and Bureau of Economic Analysis

Because user fees cannot fund all public services, taxes are necessary. However, fees constitute an important tool in policymakers’ fiscal toolkit. Because taxes have a dampening effect on the economy, policymakers should carefully consider the balance between taxes and fees to fund services.

Phil Dean is the public finance senior research fellow at the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute.